[Baltimore Sun] Dan Rodricks: ‘It’s epic.’ A Baltimore artist’s masterwork finally get its moment | STAFF COMMENTARY

Billy Pappas wanted to do something extraordinary in a world where so much of the extraordinary already exists. The closer you get to him, the more he speaks and explains, the more you understand his desire, the more you understand how he could devote eight years of his life to a pencil portrait of Marilyn Monroe.

It wasn’t enough just to sketch the most recognizable woman of the 20th century, though Pappas was thoroughly capable of doing that. He had trained at the Maryland Institute College of Art. He had a good hand for illustration.

But he wanted to break through the boundaries of art. He wanted to take drawing to a deeper dimension — beyond what the human hand had ever achieved, beyond what the human eye had ever beheld.

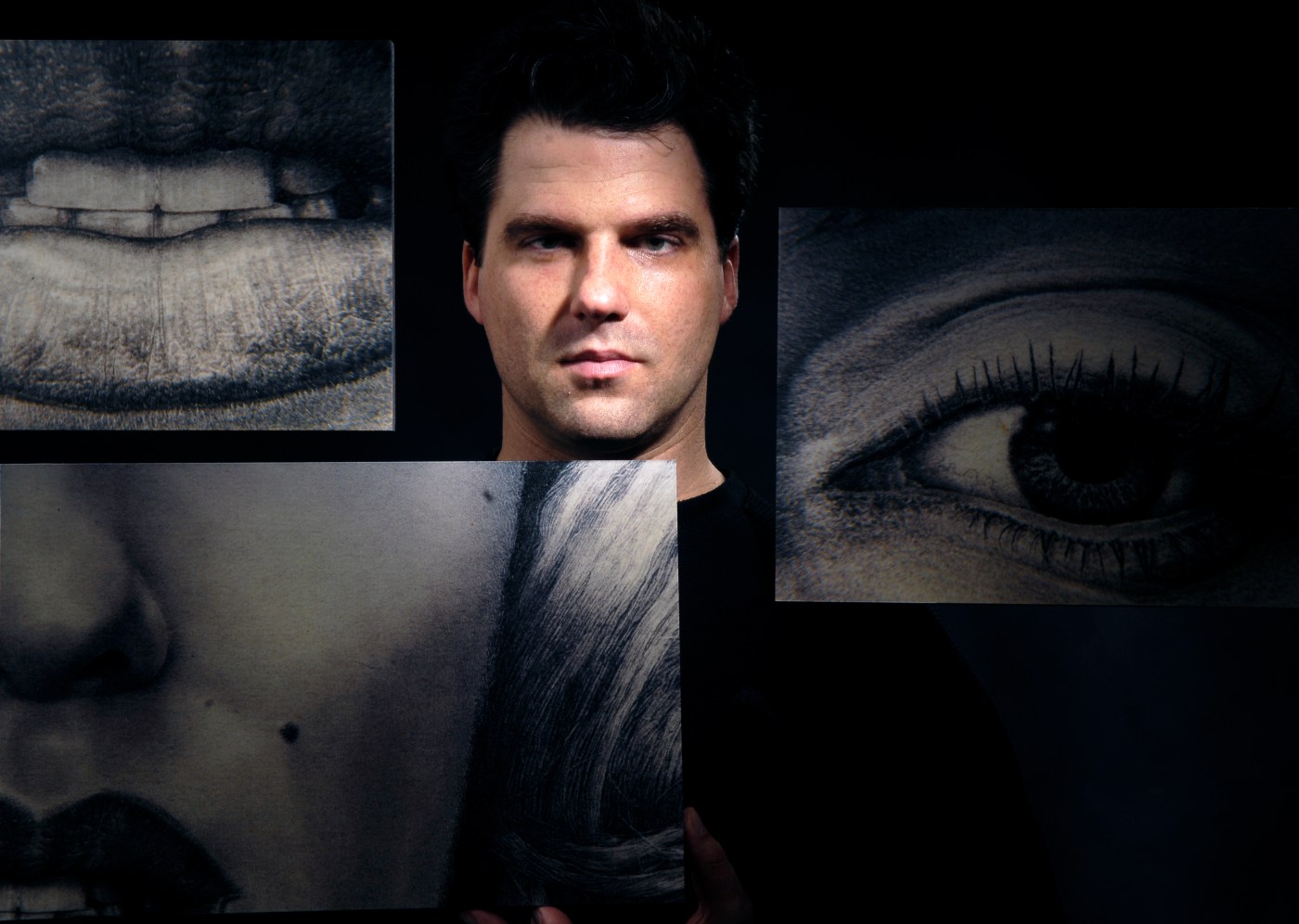

He did this with millions of fine-tip graphite marks on paper, with obsessive devotion to detail. He wore magnifying glasses as he worked long hours on the subtle contours of flesh, the corners of lips, the tips of eyelashes.

He wanted to capture the fine, errant strands of hair he saw in people in real life but not in art. He found that challenge in a 1957 photograph of Monroe by Richard Avedon.

“I made a commitment to do it,” Pappas says. “It’s like a marriage. It’s not always fun, from what I hear, but you gotta stick with it. My hope was, if I stuck with it, I would accomplish what I set out to accomplish and that I would feel great.”

The result was something that, from a distance, looks like a good photo-realistic rendering of the world’s most famous blonde. But, up close, the Pappas “Marilyn” has startled people with its level of detail.

Gary Vikan, former director of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore and an art historian, said he had “never seen anything like” Pappas’ “Marilyn.” It has, he says, a depth of resolution “likely never before achieved in the history of art.”

Now Vikan is the curator of the first formal exhibit of Billy Pappas’ “Marilyn.” The drawing can be seen through mid-May in the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center in Washington, billed as “A Drawing Like No Other.”

Pappas is thrilled to finally have his opus on display.

After all, he stepped away from his vertical drawing board in 2003, having worked on “Marilyn” for more than eight years, about a quarter of his life at that point.

It was around that time that Billy Pappas first became a story. A filmmaker named Julie Checkoway made him the subject of her documentary, “Waiting For Hockney.” Shot in Baltimore, New York and Los Angeles, the film was about Pappas’ desire to have David Hockney, one of the world’s most accomplished and influential contemporary artists, view his drawing. More than that, Pappas hoped for confirmation, affirmation or maybe, eventually, a commission for a new piece.

“What I really wanted to know from Hockney was, ‘Did I have what I thought I had?’” Pappas says.

The answer is complicated.

Pappas came away from his nearly five-hour meeting with Hockney with the belief that he and “Marilyn” had made a positive impression. But toward the end of “Waiting For Hockney,” there are some snobby comments from Hockney’s assistant about how Pappas picked the wrong subject and that his work too much evokes the realism achievable with a digital camera.

There’s also an inference that Pappas spent way too much time on the work. In a 2009 radio interview, Hockney uses the words “quite amazing” to describe “Marilyn,” but he also suggests that Pappas do “some quickies,” dismissing the artist’s patience and rigor with subtle ridicule.

(One wonders what Hockney might have told Leonardo da Vinci; some historians believe da Vinci worked on the Mona Lisa from 1503 until close to the end of his life in 1519.)

Pappas is a working-class guy from Baltimore who has mostly tended bar, waited tables and worked as a maintenance man. It’s possible he expected too much from Hockney, a famous and wealthy pop artist noted for painting with bright colors. Ultimately, it was just one man’s somewhat ambiguous opinion of another’s work.

It’s true that, from a distance, there might be nothing extraordinary about “Marilyn.” It is a work of art that comes with an asterisk; you need to know the story a bit before you approach it. And, indeed, you must approach it to fully appreciate it.

Years ago, when Vikan was still running the Walters, I had the truly extraordinary experience of one of Monet’s paintings of haystacks. Up close, it was a mess of splotchy colors. But seen from 10 or 20 feet away, it became haystacks in late-summer light.

With Monet, it’s best to look from a distance. With Pappas, you want to be close. Seeing it in person is essential.

“It’s epic,” says Vikan. “And as something that’s epic, it deserves to be seen. … It’s puzzling. It’s almost disturbing. It’s hard to know how to look at it. People have very different reactions.”

Finally getting an exhibit of “Marilyn,” his masterwork, gives Pappas hope for the next stage of his creative life.

“I’m an optimist,” he says. “So I’m gonna believe that I’m gonna meet somebody who would either buy ‘Marilyn’ or commission my second one.”

His next subject, he says, will be abolitionist Harriet Tubman. He expects she’ll be eight years in the making, too.

Detail from “Marilyn” by Billy Pappas. Digital image by William A. Christens-Barry, Equipoise Imaging, LLC.